The American Civil War, or also the War of the North against the South, was a conflict in the United States of America from 1861 to 1865. Despite the fact that mass emigration from Central Europe began about 10 years later, traces of Slovaks, or people originally from the territory of today’s Slovakia, can be found in this conflict as well. Most of the participants were Hungarian emigrants who left Hungary after the revolutionary events of 1848-49. Since the territorial core of our emigrants’ settlement is still today the industrial northeast of the USA, it is natural that they fought on the Union side. Their participation in the Union army can also be explained by ideological convictions.

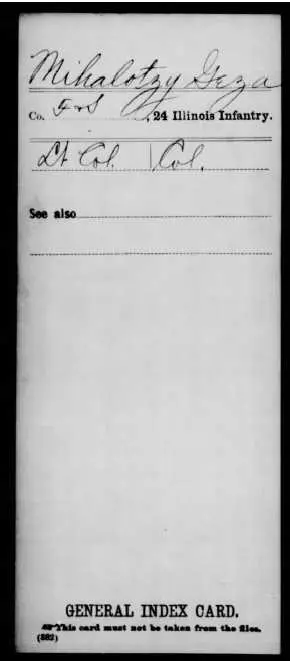

The most famous native fighting in the American Civil War is Geza Mihalóci (Geza Mihalotzy, Mihaloczy). He was born on April 20, 1825, in Veľký Varadin (now Oradea, Romania). At the age of thirteen he joined the military academy of the Austrian army in Vienna, serving in the 33rd Infantry Regiment of the Hungarian army as a sergeant-major. In 1848-49 he joined the Hungarian Revolution, taking part directly in the Battle of Pákozd. After the defeat of the revolution he emigrated first to London. In the English capital, his violent temper drove him to a duel with Lajos Kosuth’s friend Ferenc Pulszky, a native of Prešov. Mihalóci emerged from the fight with a serious injury, but immediately after his recovery he travelled to Chicago. There he initially served as a servant to Dr. František Valenta.

In February 1861, two months before the start of the American Civil War, he sent a letter from Chicago to President Abraham Lincoln: “Dear Sir, We have organized a company in our city, composed of men of Hungarian, Czech, and Slovak descent. As we are the first company formed in the United States from the above-mentioned nationalities, we respectfully request Your Excellency’s permission to call ourselves Lincoln’s Rifles of Slavic origin.” At the bottom of the letter is Lincoln’s handwritten note saying, “I am pleased to grant the above request.”

Original in the Hertz Collection

The unit was initially poorly equipped, with only 12 men leaving Chicago for the front, but gradually fought as part of the 24th Illinois Volunteer Regiment in several conflicts in Missouri, Kentucky, Alabama, Tennessee, and Georgia. The 24th Illinois Volunteer Regiment fought under his command in three hard-fought battles. At the First Battle of Perryville in 1862, the North won a strategic victory even at the cost of heavy casualties. The second battle – at Stones River – was one of the bloodiest of the conflict. It took place on New Year’s Eve 1862, won by the North.

In the last major battle at Chickamauga Bay in September 1863, Mihaloci’s army lost the battle to the Confederates. Mihalóci attained the rank of lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army. In early 1864, Mihalóci was severely wounded by a shell that tore off a piece of his palm at the Battle of Buzzard Roost. He still fought on, but a lone bullet hit him a few days later. Although he reached the unit alone, he succumbed to his wound on March 11, 1864. One of the American forts is still called Fort Mihalotzy today. He is buried in a cemetery in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

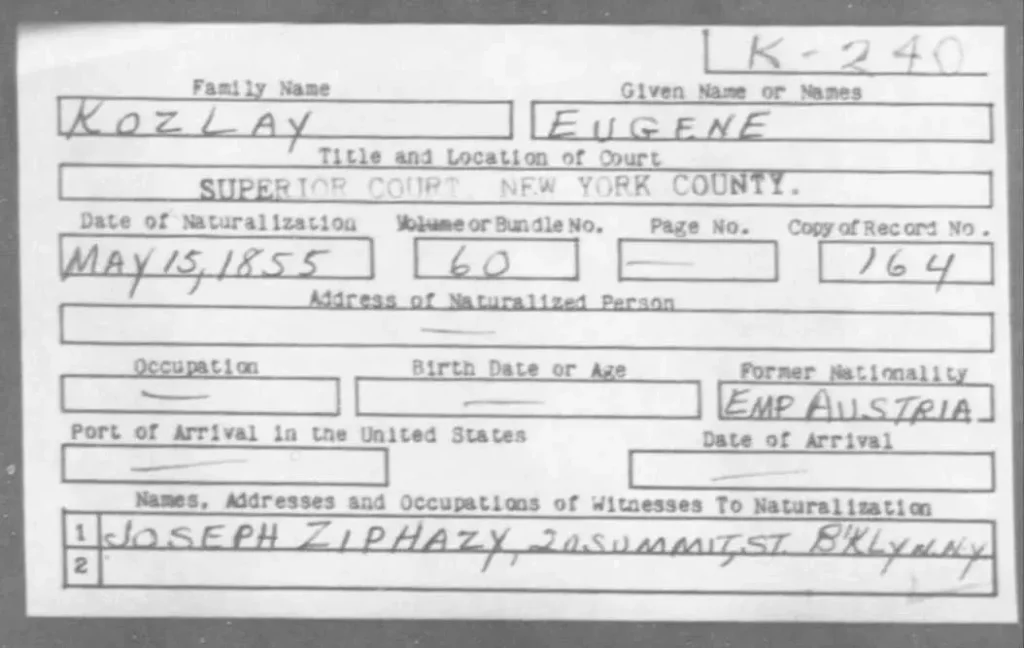

The Union general Eugen Kozlay came from Turiec, from the vicinity of Martin. He had also fought in the Hungarian Revolution before. After its defeat, he settled in a German settlement in New York. In 1861, he was offered the opportunity to form a volunteer regiment from the German settlers. He also fought in the most famous battle of the Civil War – Gettysburg. After the war, he lived in Brooklyn, where he worked as an engineer. He died in 1883.

His descendants have only recently published his almost 500-page diary, written mostly in Hungarian, but also containing one Slovak poem. Kozlay spontaneously describes what he experienced in his life “In his old age for his own amusement”. He describes his native Hungary, writes about the joy he had when he was 13 years old, when he used to ball with girls, about a voyage to America that lasted an incredible 72 days, but also about the feelings he experienced when he saw a live black slave market in New Orleans.

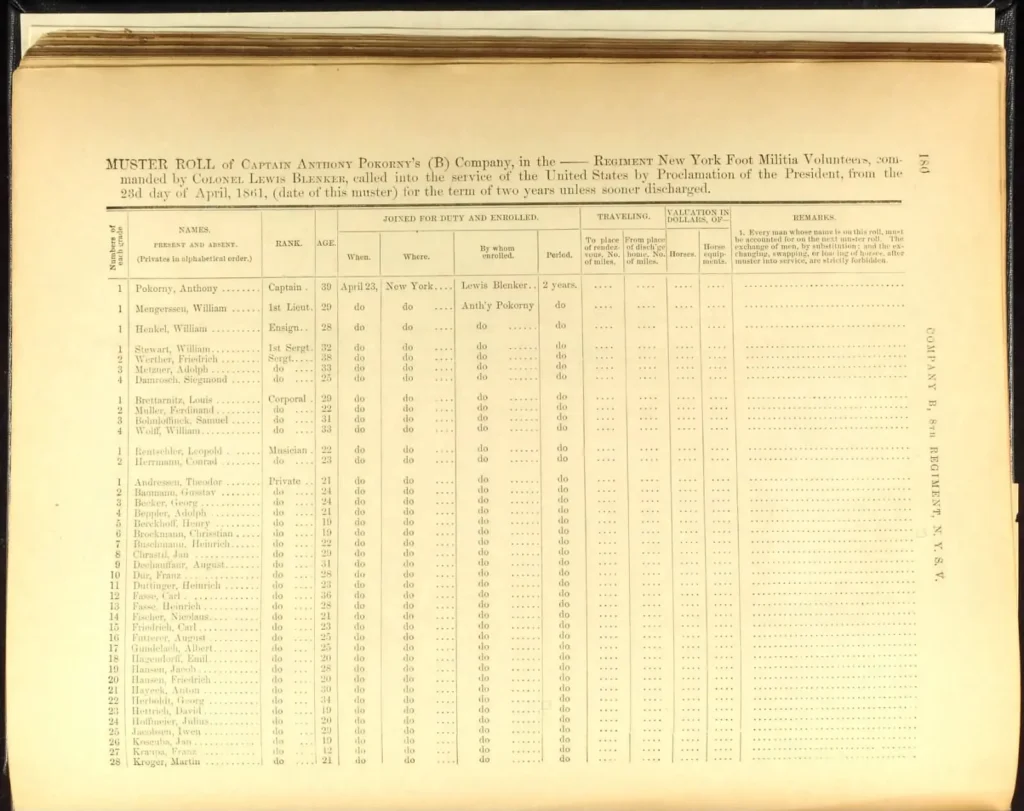

“A Slovak, devoted body and soul to his old tribe.” This is how his friend, fellow soldier and Czech volunteer Zajíček described another fighter in the Civil War with roots in Slovakia, Fridrich Werther.

He volunteered for the Union army at Lincoln’s invitation, made it to officer, was apparently educated and owned a restaurant in New York where mainly Czech emigrants liked to meet. After the war, it is said that he sold this restaurant and disappeared without a trace somewhere in the Wild West, where he was lured by the gold rush.

In the history of the Civil War, Samuel Francis Figuli is an interesting revelation. He was born in Klenovec on 31 December 1823 in the family of a tanner and grain merchant. While studying medicine in Pest, he was affected by the revolution of 1848-49. He was probably involved in the fight during which Count Lamberg, the emperor’s envoy to Hungary, was murdered. The Austrian authorities issued an arrest warrant for Figuli on suspicion of involvement in the murder: “The said was born in Klenovec, in the county of Gemer in Hungary, he is about 25 years old, studying surgery, then honvéd, of slender tall stature, light hair, weak beard.”

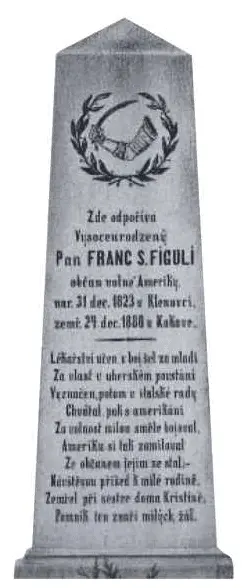

Figuli fled to Turkey, reportedly fought in the Crimean War and made a pilgrimage to Palestine. He then took part in the struggle for the unification of Italy, until he ended up in America. He fought in the Civil War on the Union side. His participation in the Civil War is confirmed by the text on his tombstone, “He then fought bravely with the Americans, he fought bravely for freedom, he loved America so much that he became a citizen of it.”

After the war, he is said to have worked as a doctor and even owned a plantation. He also allegedly undertook an expedition to the northern polar regions, as a photograph of him in polar gear has survived. A remarkable story from St. Louis, where he was supposedly insulted by an influential American who called him a poor emigrant and a “dog-head”, for which Figuli challenged him to a sabre duel. He killed the American in it, so he had to move to Virginia, where he set up a tobacco farm.

In 1876, weakened and ill, he returned to Slovakia, where he died four years later. In Kokava nad Rimavicou there is a street named after Figulis. We can also find his grave there, which reads: “Here rests the highly born Mr. Franc S. Figuli, citizen of free America.”

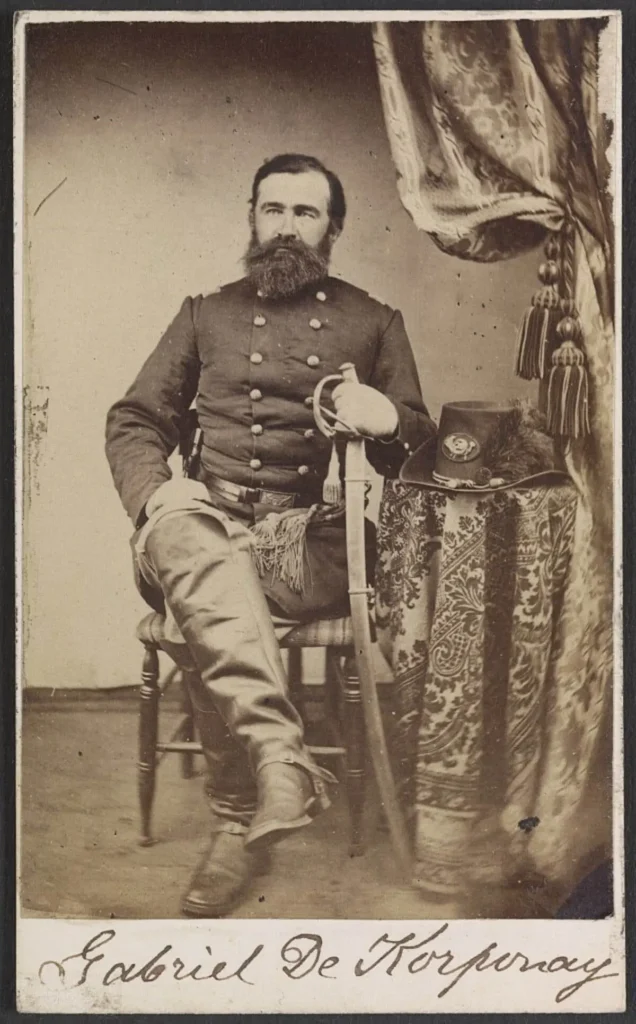

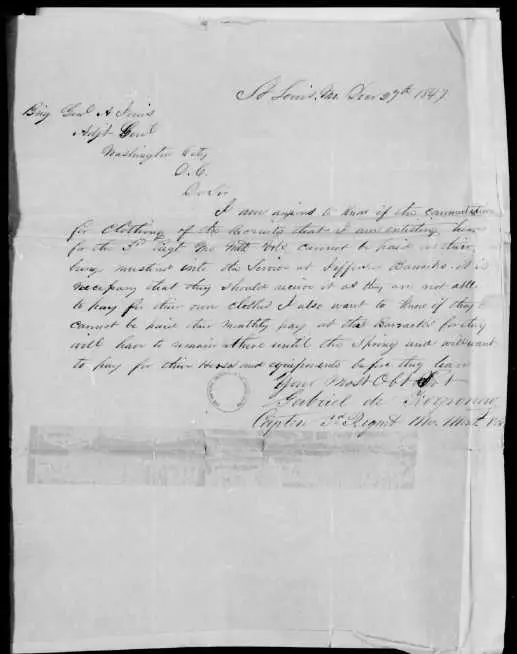

Colonel Gabriel Korponay, also known as Gabriel Krupinský in Slovak exile literature, was born on 25 March 1821 in Chym near Košice in the family of a local landowner Štefan Korponay and Johana Farkas. This renowned polka dancer, diplomat, and cavalry commander during the Mexican-American War and the Indian fighting first organized volunteers in Philadelphia after the outbreak of the Civil War. Subsequently, with the rank of lieutenant colonel, he became a member of the command staff of the 28th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, which distinguished itself greatly on October 16, 1861, with a successful deployment during the fighting for Bolivar Heights Ridge in present-day West Virginia.

Later, companies under Gabriel Korponay succeeded in an artillery show of force at Point of Rocks on the Maryland frontier on December 19, 1861, which did not escape the notice of the contemporary press of the day: ‘Point of Rocks, Thursday, December 19. At ten o’clock in the morning a battery of rebels, with a force of three guns, flanked by about two hundred soldiers, suddenly commenced shelling the camp of Colonel Geary’s Pennsylvania regiment. About twenty well-aimed shells struck the camp, the first within a few feet of Lieutenant-Colonel De Korponay, who was in command. Six companies were well posted and fortified in camp. A battery of the 28th Regiment opened fire with two guns, the first shell destroying one of the rebel guns, the second striking their centre. Our battery then opened fire, silencing all their guns, and driving off the fourth, which was to reinforce them. The rebels were driven from their position and retreated. There were at least fourteen dead and many wounded on their side. Our side did not lose a single man. The battle lasted over half an hour. Finally, after driving the rebels out, the victors turned their cannon on some houses near the old furnace on the Virginia side, where about 150 rebels were hiding, and drove them out, killing and wounding many. The guns were admirably manned.” Reported the next day by the New York Times.

Finally, on April 25, 1862, the then 41-year-old Korponay became commander of the 28th Pennsylvania Infantry, overseeing the holding of strategic areas – the Manassas Railroad and the passes in the Blue Ridge Mountains. “Soldiers of the 28th By the providence of God, I assumed command of this noble regiment composed of the best men of the army. I sincerely pledge myself always to strive for justice.” He stated in a speech addressed to subordinates. Gabriel Korponay’s last major assignment during the American Civil War was commanding the military camp at Camp Banks in Alexandria, Virginia. This was a so-called exchange center for paroled Unionist prisoners, but they were not allowed to participate in further military service until they were officially exchanged for enemy prisoners. Korponay saw to the best possible conditions in this facility, supporting, for example, the establishment of a camp theatre and organising various sports and games activities.

By October 1862, well into Korponay’s command, there were over 3,500 men at Camp Banks. Command of the camp brought with it all sorts of responsibilities; on December 1, 1862, Colonel William Hoffman, the Commissary General of Prisoners of War, wrote to Korponay instructing him to use what was known as the more economical Farmhouse Cauldron in cooking, which was supposed to be preferable to the conventional camp kettles, since one 40-gallon kettle cooked food for 100 men. Korponay was to order from the supply department a horse for the sawmill so that the wood for the stove could be cut better and especially more economically. The camp officials were to receive over 40 cents a day, according to Colonel Hoffman’s instructions. Eventually Korponay was discharged from the army at his own request for health reasons in March 1863.

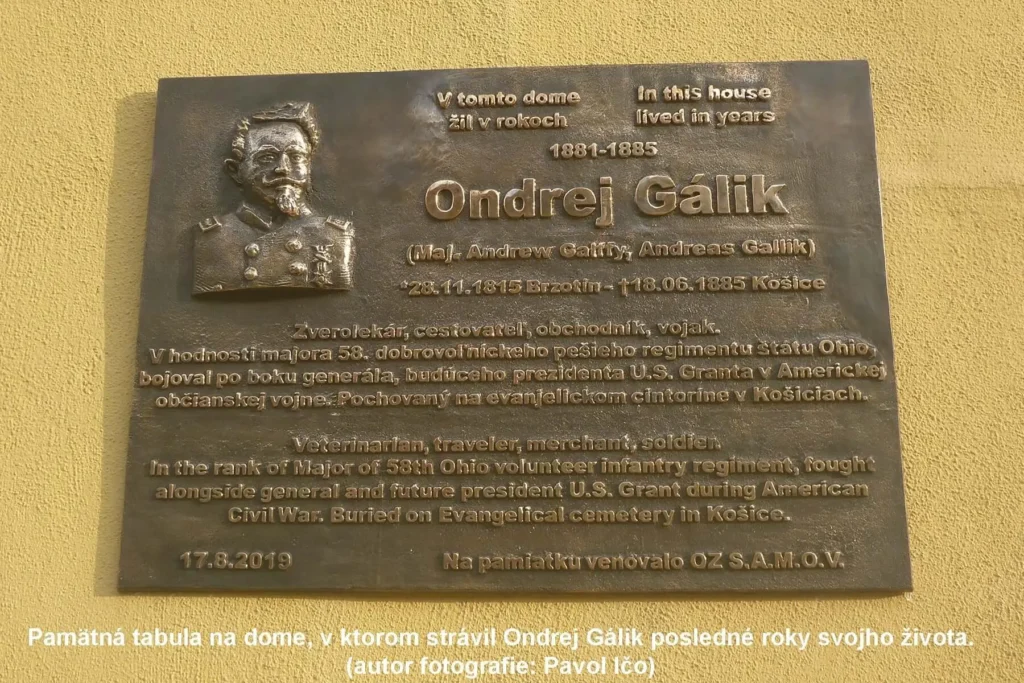

Major Ondrej Gálik of the 58th Ohio Infantry Regiment, a native of Brzotín from Gemer, also fought alongside the famous General Grant. He was born on November 28, 1815, the son of Samuel Gallik, a landowner. He studied in Rožňava and at the military school in Levoča. Eventually, however, he did not join the army and moved to Košice, where he decided to go into business. In 1843 he became a partner of the merchant Jan Samuel Schmidt and was engaged in the sale of cloth, textiles and spices. Later he married and in 1848 his son Gejza was born. In the same year he joined the revolution, but after its defeat he left his native country for fear of persecution. He first visited France, from where he made his way to the USA in February 1856. In the land across the ocean he quickly mastered English, established a fencing school in Dayton, and engaged in the itinerant cigar trade. But he was not successful in business and decided to try his luck as a gold prospector in Australia. There, too, he experienced great disappointment.

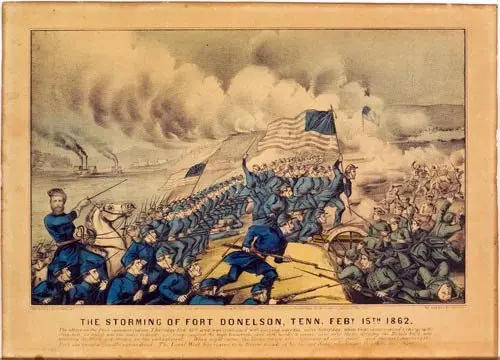

When the Civil War broke out in the US, he resolved to try a military career again. He enlisted in the Union Army and was assigned to the 58th Ohio Infantry Regiment. Less than four months later, on January 8, 1862, he became a captain. The officer, listed in contemporary records as Andrew Galfy, commanded his own Company “A” and fought in important battles in the state of Tennessee. First at Fort Donelson in February 1862, when Union ground troops supported gunboats on the Cumberland River, and then at Shiloh in April 1862 – during one of the bloodiest battles of the entire war. Gálik’s regiment did not join the fighting until the morning of April 7, 1862, the second day of the great battle, but remained under fire until 4 p.m., with nine of its soldiers killed and 43 wounded. In December 1862, a wounded Gallick was captured by Southerners during the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou on the Mississippi River. “After pushing the enemy back and reaching the first line of trenches, it became clear that further attempts would be unsuccessful. The regiment therefore retreated. Now the 58th had lost 47% of all those deployed. Amongst those killed were three officers and the brave and prompt Lieutenant Colonel Peter Dister.” War correspondent Whitelaw Reid reported on the events of December 29, 1862, which turned out unfavorably for the Ohio soldiers. As part of a prisoner exchange, Galik was subsequently released.

From 22 May 1863 to 1 August 1863, he commanded the armored ship USS Mound City, which patrolled the Mississippi River, specifically between the Grand Gulf and Hard Times locations. In October 1864, he received the rank of major, becoming second in command of Colonel Ezra Peter Jackson’s 58th Regiment. In January 1865, he retired from his military career, apparently due to lingering pain from an old wound. After the Union victory, he settled in Austin, where he served as supervisor of Tunica County, Mississippi, and in 1869 moved to Kansas City, Missouri, more than a thousand miles away. Here he began operating a private veterinary practice. A respected man, he became an American citizen, but his heart was overwhelmed by homesickness, especially for his son, whom he abandoned when he was only 9 years old. So, at the age of 66, he finally returned to Kosice, where he lived with his son, in an apartment on what is now Elizabeth Street, where a memorial plaque commemorating his life’s story was unveiled in the summer of 2019.

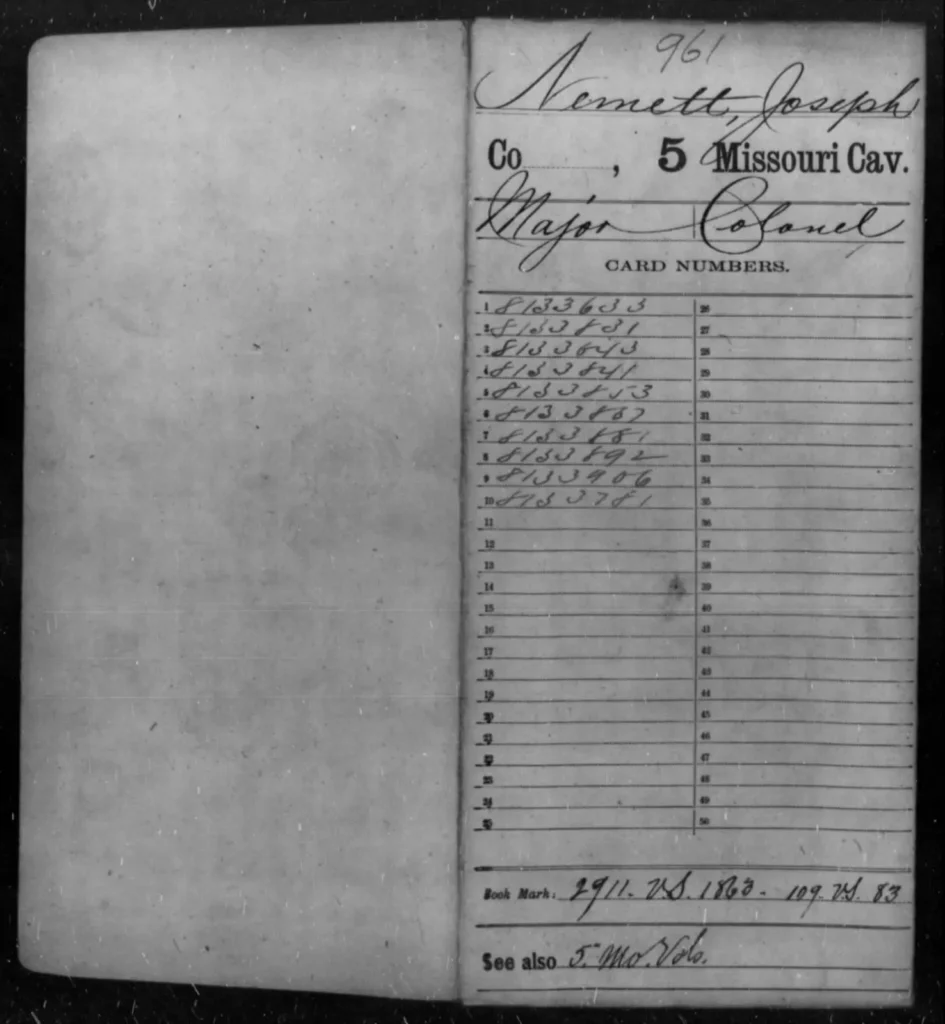

Soldiers connected with the territory of Slovakia were also represented among the cavalry, namely in the form of Colonel Joseph Németh – commander of the 5th Missouri Cavalry Regiment, also known as the Benton Hussars. Németh was born in 1816 in Lučenec. During the Revolution of 1848, he began serving in the so-called volunteer National Guard from Novohrad. Among other campaigns, he took part in the fighting at Wilson’s Creek, Missouri, on August 10, 1861, and in the Battle of Pea Ridge in March 1862, in northern Arkansas Territory, when his unit lost 17 men.

Németh (Joseph Nemett) wrote a detailed report on the deployment of his regiment. According to it, he was first in charge of forming a rear guard early on the morning of March 6, 1862, while the army marched from the army camp to Bentonville, three miles away. At eleven o’clock they sighted the enemy. Colonel Nemeth’s troops were surrounded on three sides by the Southerners, and were soon pushed back, being greatly outnumbered. Németh’s patrol did not exceed 100 men, but they observed: ‘a large cavalry force, about 500 men carrying the secession standard, rapidly approaching from the rear’. Németh therefore led “A” and “B” companies into the attack, which was to keep the enemy at a considerable distance for half an hour. The whole column thus withdrew from the town without difficulty, and on the hill further east the soldiers under the command of Joseph Németh formed into line of battle and thus faced the enemies located in the town.

During the next march the whole column was continually shelled, but at the last moment it was supported by soldiers of the 2nd and 12th Missouri Infantry Regiments, as well as two cannon, or it would probably have succumbed to the Southerners. The Confederate soldiers continued to attack, but under orders from General Franz Sigel, the soldiers around Joseph Németh continued to move. The following day, March 7, four of Németh’s companies, supported by additional cavalry units, infantry, and artillery, attacked the enemy left flank. As the Benton Hussars formed up on the battlefield, they suddenly found themselves right in the thick of the fighting, as the 1st Missouri Cavalry and 3rd Iowa Cavalry Regiments were already struggling around them with the Southerners. Throughout the day they held positions on the battlefield as a guard of artillery batteries, Company “A” additionally salvaging one lone gun that had been left on the battlefield for some time. The firing ceased about half-past six in the evening, but the Benton Hussars and two other mounted companies also spent the night on the battlefield. Finally, on 8 March, Joseph Németh’s horsemen provided protection for the left flank until the troops reached the Elkhorn Inn building: ‘We were ordered to halt there, and in the afternoon we were sent in pursuit of the enemy, capturing 15 prisoners. In the evening we reached the camp and there we remained.” Colonel Németh’s report ends. At that time the 5th Missouri Cavalry Regiment was incorporated in General Samuel R. R.’s Army of the Southwest. Curtis. The Battle of Pea Ridge was a fairly significant Civil War encounter, due to the victory of the northerners, northern Arkansas and the j

Among the artillerymen was listed Major Matej E. Ruzicka (Rozsafy), a native of Komárno of Czech origin and a graduate of the Vienna Pázmany, from the 1st Light Artillery Regiment from West Virginia. More specifically, from October 1, 1861 to April 18, 1862, he served in Battery “B”, which also participated in the artillery show of force at Kenstown in the Shenandoah Valley on March 23, 1862, when, after several attacks by the Northerners, the Southern General Jackson had to retreat.

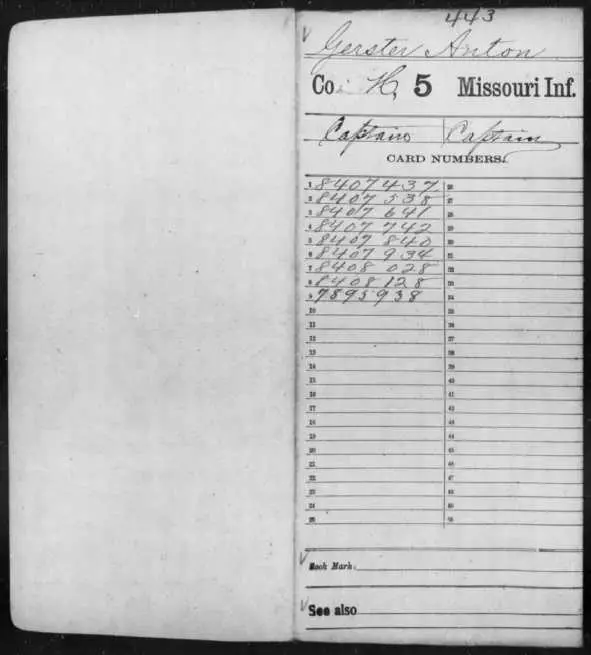

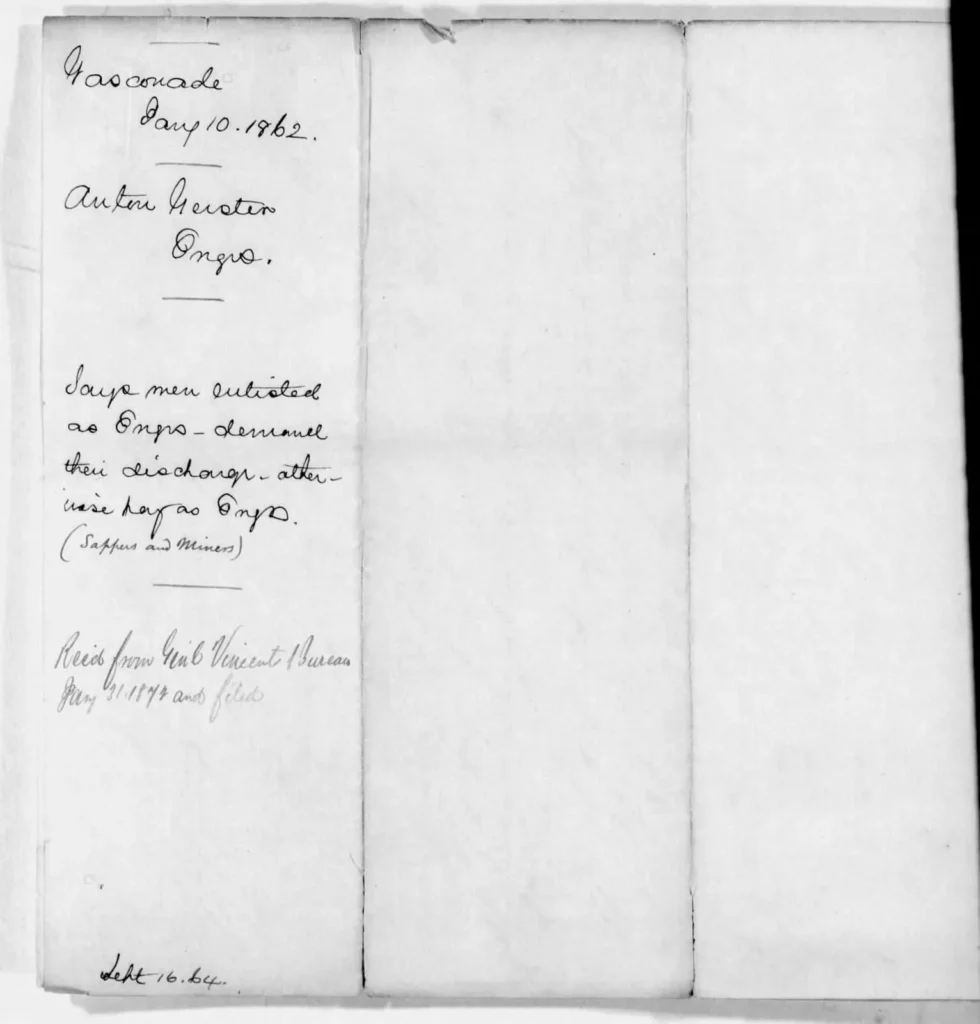

Another native of Slovakia, a member of the well-known Gerster family from Košice, Captain Anton Gerster (Košice, 7 June 1825 – San José, California, 2 June 1897), first an officer of the 5th and later the 27th Missouri Infantry Regiment, offered his technical knowledge to the Union. Anton studied in Košice and at the Technical University in Buda. Like most of our heroes, he fought in the revolution in Hungary in 1848-49. After its defeat, he fled to the United States, arriving there in May 1852. Thanks to his technical talents, he worked on important constructions such as the Brooklyn Suspension Bridge.

He was very active in the Civil War, for a time even operating the so-called Gerster Independent Engineer Company, which provided technical support to troops operating in Missouri. Among Anton Gerster’s important tasks was the inspection of forts, even those captured after battles with the Southerners. General John W. Davidson reported on his division’s deployment during the successful capture of Little Rock, Arkansas, on September 10, 1863, with all important arrangements such as trenching, battery placement, and bridge laying supervised by staff officers – Lieutenant Colonel Coldwell and Captains J. L. Halley and Anton Gerster – the night before the assault.

In February 1864, work began to improve the defenses of Fort Ford Smith, Arkansas, and the local supply depots, with Gerster again overseeing the garrison’s operations. Another time, on August 20, 1864, Captain Gerster again inspected the ammunition depot at Fort Davidson, Missouri. In his opinion, although the facility was in good condition, he suggested raising the ceiling to prevent the stored material from becoming damp, thus achieving an aerated interior and providing drainage for the premises. A month later, General Thomas Ewing Jr. unable to resist General Sterling Price’s Southern forces, ordered the ammunition depot at Fort Ford Davidson blown up and retreated toward St. Louis. Gerster was a member of the 27th Missouri Infantry Regiment by September 9, 1864. After the Civil War ended, he lived for a long time in New York City, then settled in California, where he died in 1897.

Cornelius Fornet (1818 Stráže pod Tatrami – 1894 Vác) was also a fighter in the Union army.

After the defeat of the Revolution of 1848-49, he fled to the USA, arriving there on 9 December 1849. Immediately after his arrival, Fornet published his first book in English on the Hungarian Revolution. Later, Cornelius Fornet went to California, where he bought a silicon and gold mine, which he sold at a profit a few years later. In 1852, Fornet married his fiancée in Europe, returned to the U.S. where he settled in New Jersey and began farming.

During the American Civil War, he served on the Union side as a major general in John C. Frémont’s army. He was seriously wounded at Jefferson City, Missouri. After his recovery, General Henry W. Halleck sent him to New Jersey to organize the 22nd Regiment of Volunteer Infantry. Fornet became its first colonel. After the war in 1867, Fornet returned to Hungary, working in a salt warehouse in Mainz. He died in Vac in 1894.

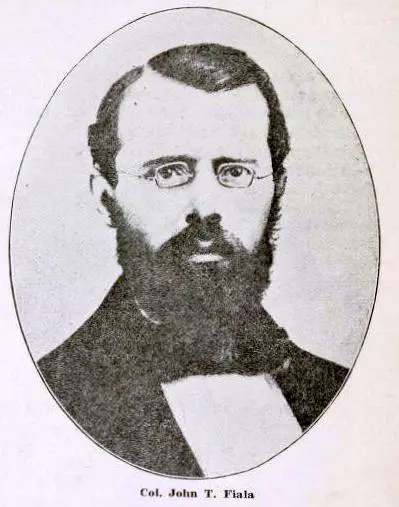

Other personalities originally from the territory of Slovakia who linked their fate with the Civil War in the USA included : Ján Fiala (1822 – 1911) – commissioned into the army as a surveyor and commissioned to draw a map of Missouri and was in charge of the plan for the defense of St. Louis

Baron Theodore Maiteny of Nitra – Major under General Frémont

Bernard Šimík – member of the Lincoln Rifles, physician

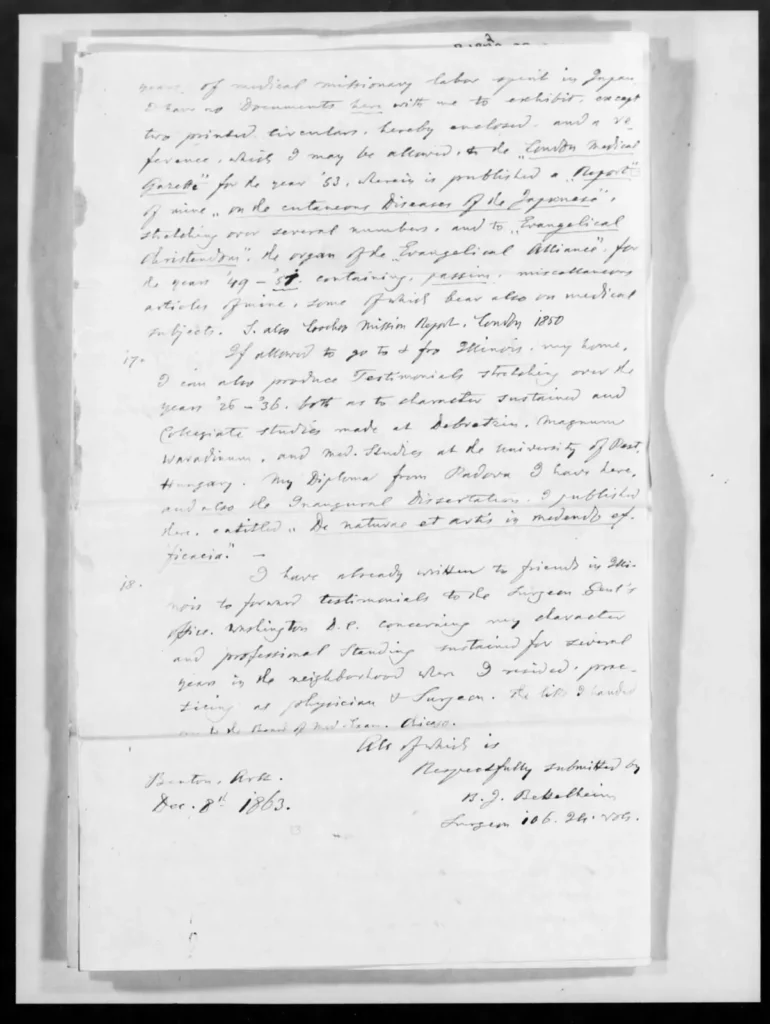

Karol Semsey (1830 Kračúnovce – 1911 New York) – Officer in the American Civil War. He also fought in the Crimean War near Sevastopol on the side of the British. He was a major in the 45th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment. After the Civil War, he went to New York, where he became a leader of the “Hungarian Society”, which was formed in 1865. He worked in the Immigration Office, where he came into contact with a large number of emigrants from Hungary. Bernard Bettelheim (1811 – 1869). Born in Pressburg, he was of Jewish origin, later converted to Christianity. He studied in Great Varadin, Debrecen and Budapest. He received his medical education at the University of Padua. From August to December 1863 he served as a surgeon in the 106th Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry.

Source:

ČERVENKA, Juraj. Spod Tatier do boja proti rebelom. Vojaci zo Slovenska v uniformách Únie. In Historická revue, 2021, roč. XXXII, č. 10, s. 34-41.